A smuggler tells

In Switzerland everything is always legal

In the 1960s, smugglers brought tons of coffee and cigarettes from Switzerland to Italy, earning good money and filling the AHV coffers on top of that. In Switzerland, this was not called smuggling, but rather Export II.

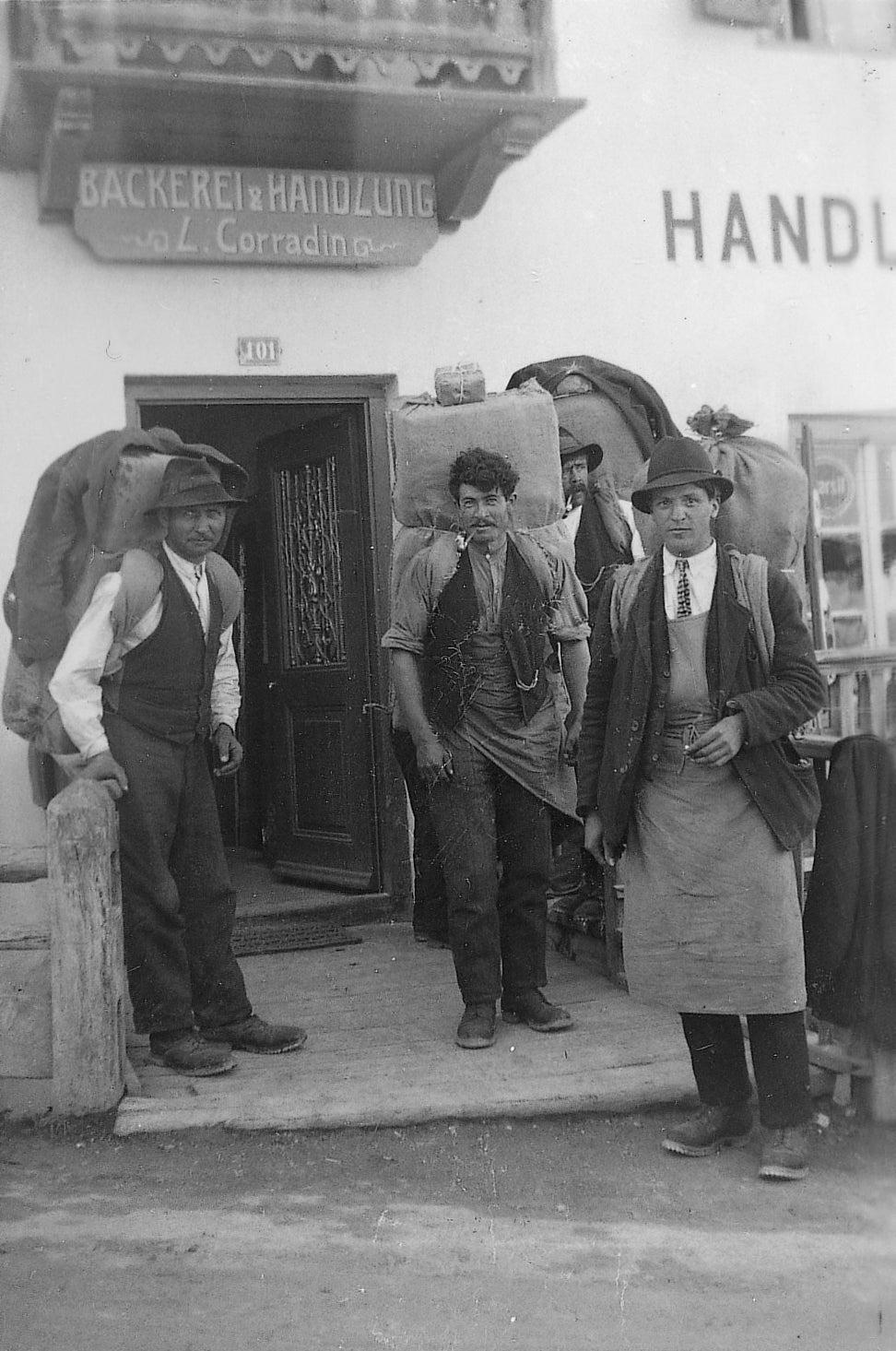

As they were saying goodbye, under the front door of the farmhouse in Lichtenberg in the upper Vinschgau, the wife also intervened. "But he only confessed that to me on our wedding night. Before that, everything had sounded more harmless." At the wedding reception, fellow smugglers put on a performance, and shots were fired. "My husband promised me he would never smuggle again." The promise was not too difficult to keep, as the lucrative years of smuggling cigarettes and coffee from Switzerland to Italy were over. Before that, from 1961 to 1972, this smuggling was highly profitable. A packet of cigarettes cost around 75 centimes in Switzerland, while the national Italian brands were about twice as expensive. In 1972, this business collapsed because the lira/franc exchange rate was no longer attractive and the Swiss tobacco tax was raised again. "The smuggler," who spent two hours telling us about the old days, doesn't want to read his name in the newspaper. But he does want to read his story. Sixteen Days' Wages in One Night "I went for the first time in 1961. I was already a few years over the minimum age of sixteen required by the Swiss. We entered Switzerland legally, with the lire notes for the purchase of cigarettes, and drove to Santa Maria. There Otto Cazin ran the office of the Basel wholesaler Weitnauer and a kiosk on the Umbrail pass. Cazin was the Export II entrepreneur in the Münstertal. Everything was legal in Switzerland, and we got on well with the Swiss customs officers. It was important that Cazin declared the export of the contraband - mostly cigarettes - by 6 p.m. It was only in Italy that everything was illegal, and you couldn't get caught there.** Either you hired yourself as a porter and received 15,000 lire (around 92 francs) from the capo for one trip. If you wanted to bear the risk as well as the load of 38 kilograms, you bought a thousand packets of cigarettes from Cazin for 131,000 lire on your own account - that's how many you carried in a pinggl, a bricolla. You would then get 180,000 lire for that in Lichtenberg or Prad - a nice profit. A forest worker earned 3,000 lire a day, sixteen times less than we did in a night. Those were the prices and wages in 1961. Later they gradually increased. You paid directly in cash, without receipts." "The smuggler" often went with the group of Hubert Riedl, the undisputed smuggling king of Lichtenberg. Did he know that with each trip he was supporting Switzerland's state pension scheme, the AHV, with 400 francs? No, this is the first time he has heard of this. "Most of the time we went in groups of seven or eight, sometimes in groups of up to eighteen or nineteen boys and men. Cazin had the Pinggl ready and packed. We preferred the brand of cigarettes 'Ernte 23', they were the lightest. We often went out down below, along the Rombach, with the heavy 'Turmac'. How did one of these walks go? After a day's work, you packed bacon, cheese, bread and a bottle of wine in your backpack and had another drink in the 'Weisses Rössl' in Lichtenberg, where the finance people also stopped off. Then we drove to Santa Maria, where things were often very lively in our local pub, the Alpina. If it was cold outside, you bought a chocolate and a juniper berry for the journey. We walked at night, we had to arrive in the dark. The most popular route was the one over the Rifair Scharte. We also chose this route for our hike, during the day and with less than ten kilos on our backs. A demanding route, with 1300 metres of ascent and 1600 metres of descent. And with a fantastic view from the saddle into the upper Vinschgau. ### **Shots around the ears** "Either we crossed the border near Müstair next to the Rombach, or a member of staff from Cazin drove us a little way up and we left Switzerland much further up. We often did two or three walks a week, sometimes six, except on Sundays, when the Swiss had a day off. We walked all year round, even in winter. When it snows, if you lose your bearings for just a moment, you're lost; you go in circles. In summer, there was less walking, as many people in Switzerland worked on an alpine pasture or making hay. Yes, you could hear bullets whistling around your ears. If you were surprised by a patrol of financiers, you would throw off your load and flee. We knew the area much better than the financiers, especially in the dark. Once we lost eighteen Pinggl. The newspaper only mentioned fifteen. It was an open secret that the financiers also supplemented their salaries a little. You walked like Italian mules, regularly, at a steady pace. It was hard work, not for mama's boys or the whiny. You didn't have to be squeamish, you had to have a certain amount of discipline. You did get smart, smarter every year. It was a man's job. The women supported us in the valley, for example when they went to tell us where and when we were meeting. The smuggled cigarettes were handed over to a chauffeur who drove them to Milan or Rome on behalf of the buyers. Yes, it was like an addiction, it gave you a feeling of superiority, of strength. We were the winners. There must be no fear, otherwise you have lost. The boom lasted for over a decade, until 1972, when cigarette smuggling over the mountains came to a halt. At the same time, conditions in South Tyrol improved, and autonomy came into force in 1972. Today, we South Tyroleans are doing well, even without smuggling. ### **A wreath for Hubert Riedl** So much for "the smuggler". Of course he also told an anecdote about the smuggling king Hubert Riedl. But only when we mentioned the name. Fanny, the almost legendary landlady of the 'Weisses Rössl' in Lichtenberg, also tells us about Hubert. "This was the smugglers' headquarters," she explains to us before she has even finished tapping the beer. "There was a back entrance for the smugglers via a staircase." We don't leave Lichtenberg without a tour of the cemetery, bowing briefly in front of Riedl's grave. And we think about bringing a wreath with a ribbon next time: "A thank you from the Swiss AHV pensioners." The Riedls group owes millions. By Ursula Bauer and Jürg Frischknecht